The CSPC Dispatch - Jan 30, 2026

In this issue, Senior Fellow James Kitfield examines the emerging contours—and mounting consequences—of President Trump’s revived “Donroe Doctrine,” arguing that a foreign policy rooted in coercive transactionalism is eroding alliances. Senior Democracy Fellow Jeanne Zaino challenges the prevailing narrative of polarization, contending that the deeper democratic crisis lies in a system structurally resistant to majority responsiveness. Additionally, Jordan Reyes explores Congress’s diminishing role in foreign policy and asks whether lawmakers are willing, or able, to reclaim their constitutional authority over trade and war.

The “Donroe Doctrine” Hits a Snag

By James Kitfield

President Donald Trump delivers remarks at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland on Wednesday, January 21, 2026, at the Davos Congress Center. (Photo Credit: Daniel Torok, White House)

It turns out that sovereign nations, not unlike people, don’t like to be bullied. Kick enough sand in their faces in the form of punitive tariffs, gratuitous insults and outright threats of military conquest, and even close allies are prone to look elsewhere for geopolitical partners, or at least a little respect. Who could have guessed?

And yet bullying has proven a central pillar of President Donald Trump’s neocolonial “Donroe Doctrine.” Another feature is petulant self-aggrandizement, as recently revealed in a Trump note to the leader of Norway: “Considering your Country decided not to give me the Nobel Peace Prize for having stopped 8 Wars PLUS, I no longer feel an obligation to think purely of Peace…” There are also repeated demands for fealty, as evidenced when Trump recently stood before international leaders at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland and lauded a cringe-worthy comment by NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte: “They called me ‘Daddy,’ right?” said Trump. “Last time. A very smart man said, ‘He’s our Daddy.’”

Perhaps not surprisingly, the essence of the foreign policy adopted by the former real estate mogul and reality TV star is values-neutral transactionalism. The art of every deal boils down to squeezing your opponent into surrendering the best terms. And when every diplomatic engagement is viewed simply as a transaction, with the goal of exerting maximum pressure to extract maximum leverage, then every interlocutor is essentially treated as a mark.

Wielded on behalf of the richest and most powerful nation on earth, and stripped of cumbersome notions such as democratic values, diplomatic norms and alliance relations based on trust, such a transactional approach to geopolitics can take you quite far for a time. Observe the many nations who held their collective noses and lined up over the past year to cut deals and mitigate the effects of Trump’s wildly fluctuating tariffs. Of course, bullying doesn’t work as well when other bullies are willing to call your bluff. That was the message last year when the Trump administration backed down from threatened 145 percent tariffs on China after Beijing responded by restricting exports of rare earth minerals critical for U.S. manufacturing.

No such luck for closer and less powerful countries, however, especially neighbors in the Western hemisphere. They have no choice but to adapt to the new reality of Trump’s “Donroe Doctrine,” an update of the 1823 Monroe Doctrine declaring hemispheric dominance. Panama? Better cough up the Panama Canal or else (“We’re going to take it back, or something very powerful is going to happen,” Trump has warned). Mexico? Our neighbors to the south suddenly find themselves on the shores of the “Gulf of America” and living under military threat (“Would I launch strikes in Mexico to stop drugs? OK with me, whatever we have to do to stop drugs,” Trump told reporters when asked if he would consider military action across the southern border). Canada? Trump continues to belittle its prime minister as “governor,” while insisting that our neighbor to the north should rightfully surrender its sovereignty and become part of the United States (“Frankly, Canada should be the 51st state, OK?” Trump proclaimed.)

Lest any of our neighbors were inclined to laugh off the resurrection of a neo-colonial doctrine of conquest and resource extraction more than two centuries after its expiration date, there was the example of Venezuela to spoil the joke. First the Trump administration unilaterally declared low-level Venezuelan drug mules “narco-terrorists” without offering any evidence or defining the term. Then it eviscerated more than one hundred and twenty-five of them in international waters with military strikes, even though the drugs they carried were most likely headed not for the United States, but rather destined for West Africa and Europe.

Then the punchline: the Trump administration captured strongman Nicholas Maduro with a targeted military strike earlier this month, after which the president said almost nothing about the illegal narcotics that presumably justified regime decapitation in the first place. Instead, Trump declared himself acting president of Venezuela and announced that the U.S. was taking control of the country’s massive oil reserves and recruiting U.S. companies to extract it.

Following the initial success of the Venezuela snatch-and-grab operation, Trump has seemed increasingly intoxicated by the use of the U.S. military as the ultimate instrument of coercion and international leverage. Despite questionable claims of having ended more than eight wars and coming as a man of peace worthy of the Nobel Prize, Trump has actually ordered at least 626 military strikes in his first year back in the Oval Office, more than his predecessor launched in his entire four-year term.

And “Donroe” is just getting warmed up.

How else to explain Trump following the hostile takeover of Venezuela by casting his acquisitive gaze on Greenland, part of NATO ally and fellow democracy Denmark? “We are going to do something in Greenland, whether they like it or not, because if we don’t do it, Russia or China will take over Greenland, and we’re not going to have Russia or China as a neighbor,” Trump told reporters at the White House earlier this month, later underscoring the threat in case anyone missed it. “I would like to make a deal the easy way, but if we don’t do it the easy way, we’re going to do it the hard way.”

To drive the threat home, Trump even trolled our allies with an image on his Truth Social platform of an Oval Office meeting supposedly with European leaders with a map in the background featuring the American flag superimposed over Canada, Greenland, the United States and Cuba, and another post depicting the president planting an American flag on Greenland.

When they were dusting off a neo-colonial doctrine more than two centuries old, the Trump administration might have considered an even older truth espoused by Sir Isaac Newton: for every action in the world, there is an opposite reaction. Alarmed by Trump’s unprecedented threats against a democratic ally, fellow NATO members France, Germany, Norway, Sweden and Holland all sent troops to Greenland under the guise of a “joint military exercise,” in what appeared an attempt to comfort a distressed ally and deter rash action by the supposed leader of the transatlantic alliance.

Faced with unified pushback by America’s closest allies, and initial signs of a revolt even among some influential Republicans on Capitol Hill, Trump backed off his threats to use military force against Greenland in his speech at the World Economic Forum earlier this month. But the star of Davos was Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney, who in a speech heard round the world declared a “rupture” in the U.S. led, rules-based international order, and encouraged middle powers to stand up to American “hegemony.” Carney’s speech prompted global political and corporate leaders in the Davos audience to rise and give a rare standing ovation.

“Every day we’re reminded that we live in an era of great-power rivalry, that the rules-based order is fading. That the strong can do what they can, and the weak must suffer what they must,” said Carney. If great powers such as the United States abandon even the pretense of rules and values for the pursuit of power, he noted, then the gains from unbridled transactionalism will eventually dissipate. “Allies will diversify to hedge against uncertainty. They'll buy insurance, increase options in order to rebuild sovereignty – sovereignty that was once grounded in rules, but will increasingly be anchored in the ability to withstand pressure.”

Matching action to words, Carney preceded his Davos appearance with a trip to Beijing to meet with Chinese President Xi Jinping, reaching a trade deal reducing tariffs and hailing a “new strategic partnership” with America’s chief geopolitical rival. He was soon followed by Finnish Prime Minister Petteri Orpo, another NATO leader, who on a recent four-day visit to China signed multiple cooperation and trade agreements, and discussed with Chinese leaders global security issues and warming European Union-China relations. Prime Minister Keir Starmer of Britain, traditionally America’s closest geopolitical ally, is currently on his own high-profile visit to China, where he will seek new trade and investment from the world’s second-largest economy as relations between the United States and its Western allies continue to sour.

The architects and namesake of the “Donroe Doctrine” mistake bluster and bullying for signs of strength, and they would have you believe that the United States will be safer and more prosperous for trying to turn back the clock more than two centuries to an era of colonial conquest and hegemonic “spheres of influence.” Better study that blueprint closely before you approve the plans.

No amount of chest thumping and trolling can gaslight history. The game of empires the Trump administration thirsts for ultimately culminated in two world wars and the bloodiest epoch in human history. From those ruins wiser men built a rules-based international order on a foundation of shared values among global democracies, sustained for over a century by mutual respect and collective action. Today that edifice is shaking because the current steward wants to tear it all down and build something more gold-plated and ostentatious in order to slap his name on it. But once it’s gone, we will surely miss the world America made.

Senior Fellow James Kitfield is a recipient of the National Press Club’s Edwin Hood Award for Diplomatic Correspondence, and the only three-time recipient of the prestigious Gerald R. Ford Award for Distinguished Reporting on National Defense.

At 250, The Polarization Myth Obscures a Bigger Problem, Lack of Responsiveness

by Jeanne Zaino

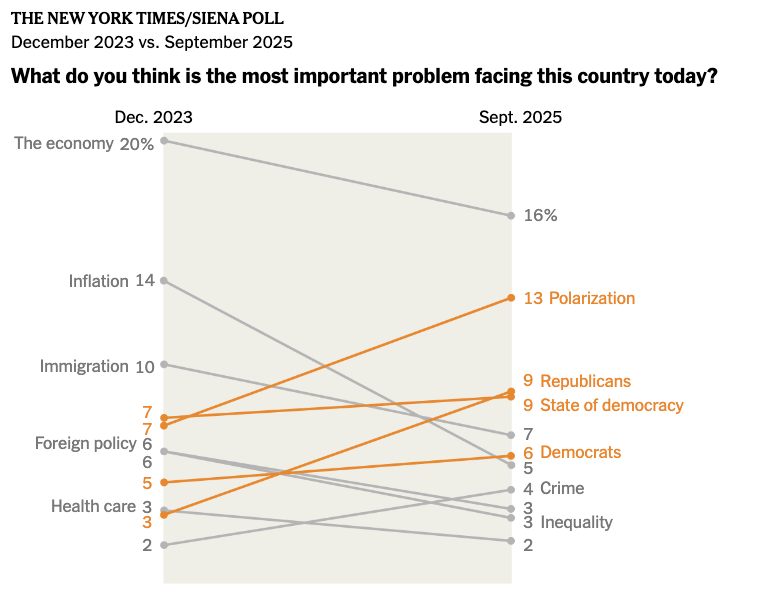

Based on New York Times/Siena polls of registered voters nationwide conducted Dec. 10-14, 2023, and Sept. 22-27, 2025. Chart shows the top categories of responses to an open-ended poll question. Numbers are rounded. By Yuhan Liu, New York Times.

“What do you think is the single most important problem facing the country?”

After the economy, increasing numbers of Americans tell pollsters the most important problem (MIP) confronting the nation is political polarization. A New York Times/Sienna poll taken last fall found that when it comes to the MIP facing America, more respondents “named polarization and the state of democracy,” than “immigration, inflation, or crime.”

This is in keeping with findings from other pollsters including Gallup, the Chicago Council on Global Affairs and the Weidenbaum Center Survey (WCS), all of whom have found that Americans’ belief in national polarization has eclipsed previous benchmarks. According to Gallup, “a record-high 80% of U.S. adults believe Americans are greatly divided,” up more than 10% from 2012.

Almost 9/10 Americans report being tired of the political divisions and nearly as many (86%) say they are exhausted by the division in America.

These findings have prompted many to ask why we are so polarized? What accounts for the increased divisions? Speculation ranges from the rhetoric used by elites to the new social media landscape and the education divide.

Americans’ belief in polarization may be at record highs, however the research finds that the perception of division does not track with reality. In fact, the data shows that Americans are far less divided on key policy issues, interests and values than most people believe. The ‘gap’ between reality and perception when it comes to the degree of disunity in the nation, is often described as the ‘polarization myth.’

“We are told America is divided and polarized as never before,” writes Professor Tim Wu. “Yet, when it comes to many important areas of policy, that simply isn’t true.” Likewise, in an essay published last summer entitled “Americans are not so polarized,” Kristen Soltis Anderson makes a similar case: “few Americans live at the extremes... only 13 percent of Americans hold views that could be categorized as ‘strong liberal’ and only 11 percent as ‘strong conservative.’”

Given these findings, the question we should be asking is not why we are so polarized, but rather why the government so often fails to act on the many things on which majorities and super-majorities agree? Why in the oldest democracy in the world are the wishes of the majority so often ignored?

The answer is the system; the US has a governmental system that has largely succeeded in doing what it was originally designed to do, i.e., frustrate majority rule and responsiveness. The Framers designed the system this way for a very important reason, to preserve liberty. On the 250th Anniversary, it is incumbent on all of us to consider the implications of this structure on our lives today and grapple with whether it still makes sense or should be reformed?

The positive ramifications of a divided system are well known, it helps preserve freedom and ensure that when policies are adopted, they are well vetted and widely considered. Also important, are the negative implications, including the fact that it impedes responsiveness to the majority will. While separated powers were supposed to stave off unwise policies, over the decades it has also worked to ensure that necessary, wise, widely supported, and just policies are ignored as well. Wu mentions several of these, including numerous policy ideas that are agreed to by super-majorities, such as lowering drug prices, net neutrality, higher taxes for the ultra-wealthy, etc.

There are many examples of separated powers impeding responsiveness, one recent hot-button issue is illegal immigration. Even though for decades people across the political spectrum have agreed that the U.S. immigration system is in crisis, the federal government has been unable to work via regular order to rectify the problem. President Obama, like President G.W. Bush before him, came to office in 2009 convinced that something had to be done about immigration. Throughout his campaign, Obama promised to protect the most vulnerable population, the undocumented young people who were brought to the United States as children. His concerns about the ‘Dreamers’ were shared by most Americans. Polls at the time showed that three quarters of respondents supported legalization for people who were brought to the United States as children.

Several years into his administration, however, an exasperated Obama finally declared he could no longer wait for congress and he launched an initiative called “We Can’t Wait.” In the absence of congressional authorization, he proceeded unilaterally. Despite concerns about the constitutionality, he issued an Executive Order ‘Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals [or DACA] to protect the dreamers – a step that even he confided was neither the ideal way to protect these young people.

Obama was not alone in his efforts to address this challenge, as Louis Fisher writes, “efforts to pass legislation dealing with immigration have persisted for many decades, often leading to deadlocks within Congress in the search for bipartisan agreement. Both Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama attempted to pass immigration legislation, without success.”

While Obama ultimately took unilateral action, comprehensive immigration reform must come from Congress. In the decade since Obama left office, however, Congress has taken no such action, and the problem has grown more acute.

This helps explain why immigration has played a key role in each subsequent election including the last election when a poll found that, for the first-time, immigration surpassed inflation as the most important policy issue on the minds of voters. Despite this, in early February 2024, a bipartisan bill described as the toughest piece of border security legislation drafted in over one-hundred years, died after failing to garner the votes necessary to override a filibuster in the Senate.

As with his predecessors, immigration was at the forefront of all three of President Trump’s campaigns and he began his first and second terms promising to address the issue. Since returning to office early last year, Trump has arguably moved more forcefully on immigration than his predecessors, but he has done so using the same tactic as Obama, EO. Unable or unwilling to push legislation through congress he has taken the controversial tactic of exerting enormous and questionable Executive authority that, even the White House’s private polling, shows is costing him support amongst key demographics.

Regardless of what you think about Trump and his immigration tactics, the fact remains that when he came down the escalator to announce his candidacy in 2015 he chose to focus much of his attention and subsequent campaign on the issue of immigration because like Bush and Obama, and later Biden, he recognized how fed up Americans were with the lack of governmental action on this issue. He recognized that large majorities of Americans and members of the public and officials on both sides of the aisle agreed that illegal immigration was a major problem that government had been unable to address via regular order (by way of congressional legislation). His promises, first of a wall and second of closing the border and getting tough on illegal immigrants in the country, resonated with voters who after decades of a lack of action, were fed up with their government’s inability to address the issue.

Lack of governmental responsiveness has major spillover effects, including (but not limited to) allowing well-placed minority interests to supplant those of the majority, encouraging the Executive Branch to take matters into their own hands, and increasing public frustration that can result in rising feelings of inefficacy, citizens tuning out or fighting back.

Jeanne Sheehan Zaino is professor of Political Science, Senior Democracy Fellow at the Center for the Study of the Presidency & Congress and Visiting Democracy Fellow at the Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation, Harvard Kennedy School. This piece draws on themes in her latest book, American Democracy in Crisis (Palgrave, 2025), and her Substack newsletter, The New Realist. It is the sixth in a series on reform marking America's Semiquincentennial.

Will Congress Defend the Constitution?

By Jordan Reyes

U.S. Capital Building on September 5th, 2013. (Photo Credit: Martin Falbisoner)

The U.S. Constitution makes clear Congress’s foundational powers in the realm of foreign policy, assigning it primary responsibility for regulating foreign commerce, ratifying international treaties, and deciding when the nation goes to war. Article One of the Constitution establishing the legislative branch of the federal government, in fact, explicitly grants Congress the power to levy duties and tariffs, raise an army and navy, and make declarations of war.

These provisions were not incidental. The Framers of the Constitution were shaped by their experience with monarchical authority. As a result, they sought to prevent unilateral executive control over decisions that could entangle the nation in war or economic retaliation. Despite this careful design, however, modern American foreign policy increasingly operates outside that framework established by the Founding Fathers, with Congress’s role diminishing over time.

The shrinking of Congress’s role in foreign policy has occurred gradually rather than through a single constitutional change or policy deviation. Especially since World War II, as

America’s global presence expanded, so too did presidential influence over foreign affairs, with chief executives increasingly relying on executive agreements, emergency authorities, and broad interpretations of presidential prerogative to increase their power. According to the Congressional Research Service, for instance, the United States has entered into thousands of executive agreements, with over 90% of all international agreements being executive agreements. While these agreements are legally recognized, they are not held to the level of legislative scrutiny originally envisioned in the Constitution for binding international commitments.

Although tariffs are constitutionally grounded in Congress’s taxing and commerce powers, lawmakers have delegated substantial authority to the executive branch through statutes such as the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 and the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) of 1977. Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act, for example, allows the president to impose tariffs on national security grounds. That provision was used by President Donald Trump in 2018, and again in 2025, to levy tariffs on steel and aluminum imports, including from close U.S. allies such as Canada and the European Union.

More recently, President Trump has asserted authority to impose or threaten punitive tariffs unilaterally for objectives beyond security concerns. These claims have raised constitutional questions that are now the subject of legal challenges, with the Supreme Court expected to clarify the scope of presidential authority over tariffs, though the timing and scope of that decision remains unclear.

Regardless of the Supreme Court’s eventual ruling on tariffs, the broader trend is clear. Many powers that were once tightly within the grip of Congress are increasingly exercised by the executive with very limited legislative input. Making the issue even more controversial, the Trump administration has imposed tariffs in ways that are in tension with international legal principles. During recent negotiations between Trump and European nations regarding U.S. attempts to acquire Greenland, for instance, the president threatened punitive tariffs before walking them back. Some experts claimed such threats violated international legal principles of sovereignty and territorial integrity contained in the U.S.-ratified United Nations Charter.

Certainly, the Framers anticipated the dangers of such unchecked executive power. James Madison argued that the power to impose economic burdens and initiate war should not reside in the executive alone. In practice, however, modern presidents have increasingly rejected a narrow interpretation of the Declare War Clause, arguing that the president’s role as commander-in-chief of the Armed Forces and responsibility to protect the nation gave them wide latitude to act without congressional authorization. Nor has Congress been eager to insert itself into issues of war, having not formally declared war since World War II. Instead, Congress has relied on resolutions such as Authorizations for the Use of Military Force, which, while valid, fall short of an official declaration of war.

At times, Congress has attempted to reassert itself, most notably through the post-Vietnam War Powers Resolution of 1973. However, enforcement has been inconsistent, and successive administrations have questioned the Resolution’s constitutionality and ignored its reporting requirements altogether. A major consequence of the abdication of Congressional responsibility can be seen in presidential actions that continually test the bounds of executive power and weaken accountability when major foreign policy decisions are made without legislative input.

Perhaps most importantly, each time Congress surrenders its institutional prerogative to the executive helps normalize the growing imbalance in a system reliant on a separation of powers to properly function. The central issue is not whether presidents will continue to test the boundaries of their authority, because history clearly suggests that they will. The more pressing question is whether Members of Congress have the collective will to fight to reclaim their constitutional role in matters of trade, taxation, and war. Absent that determination, the current imbalance in the separation of powers will only worsen to the detriment of a republican government. In the final analysis, the Constitution cannot defend itself, but Congress can.

Jordan Reyes is an intern at CSPC and a senior at the George Washington University.